I love Ray Bradbury.

When he died, I put my head on my desk and wept. He’s one of those writers, the kind of writer whose words are like having a conversation with your best friend. His books and stories are like being captured in a sudden sunshower, or watching the Perseids spark across midnight, or standing at the edge of the Grand Canyon on a blazing afternoon. He is fantastic and marvelous and awesome and wonderful, but in the deepest meaning of those words, where the fantastic soars beyond the mundane and marvels, full of awe and filled with wonder. He was a master storyteller, and a joyous dreamer, and a hopeful cynic. I love his books, and I return to them frequently.

Fahrenheit 451 is one of my favorites. I named my dog Faber, after the retired English professor who explained the importance and necessity and meaning of books to Montag. (My dog, by the by, is not nearly so profound, but he is skittish, and he barks with immense alarm whenever my neighbor comes home.) If I had to pick a book to be my motto, or a book to give to a complete stranger, or a book to tattoo across my limbs and torso, it would probably be this one.

If you’ve never read this book, you have seriously deprived yourself.

Fahrenheit 451 is about book burning. But the thing that makes this book so immense, is that Bradbury tells us that books are NOT IMPORTANT as things in and of themselves. It’s not the books that matter, he has Faber say, it’s what’s IN the books. The bookness of a great book is the soul, the ideas, the meanderings and thoughts and figuring out the universe and figuring out humans and all the magic and terror of being alive. Books are not important, but bookness, the stuff of the book, is essential to being human and alive. Bookness is creative lassitude, it’s a rocking chair on the front porch, it’s talking until midnight, it’s a cup of coffee or tea, it’s a daydream on a walk in the afternoon. When books are burned, bookness is burned. And people, with nothing to think about, are distracted with frenzy and placated like cows.

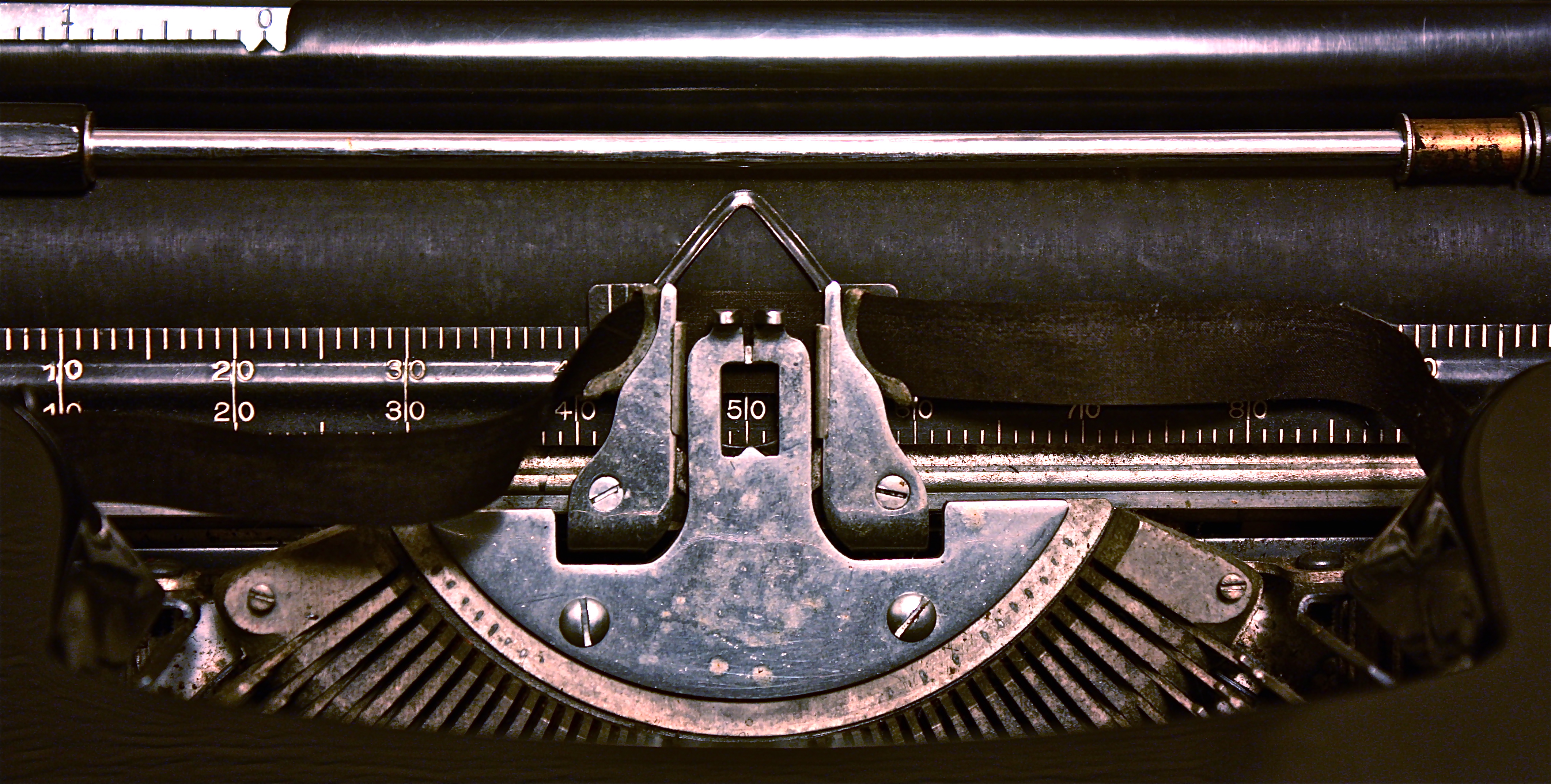

In the epilogue, Bradbury writes that his subconscious was sneaky; it helped him choose the names of Montag, a paper company, and Faber, a pencil manufacturer. I think his subconscious was even sneakier than he thought, because Faber was the pencil manufacturer whose imported pencils caused Henry David Thoreau, also a pencil manufacturer, and another great humanist, to shift his business focus to selling graphite, which was used in typesetting.

I think Bradbury’s subconsciousness was trying to make sure we knew that books are the quiddity, the essence, of life. It’s not technology, or idleness, or television that Bradbury rails against in 451, it’s mindlessness. It’s throwing away life by not thinking, by constantly distracting yourself, by not being mindFUL. It’s not paying attention. It’s not allowing ideas to simmer at the back of your mind and it’s not being creative and it’s not living actively. Technology is merely the means for passivity in 451, and books are all the means for bookness.

Whenever we burn books, or ban books, or censor books, in other words, we burn and ban and censor ourselves. “Manuscripts,” another Master of quiddity claimed, “don’t burn.” And he was right; they don’t. But we can. And we do.